Kremlin authorities are still baffled by

an apparent Internet prank on October 7th which declared

Astrakhan Oblast was declaring independence from the

Russian Federation as the “

Lower Volga People’s Republic.”

![]() |

Astrakhan is thought of as the southernmost extent of ethnic-Russian settlement

and is in an historically and ethnically volatile neighborhood. |

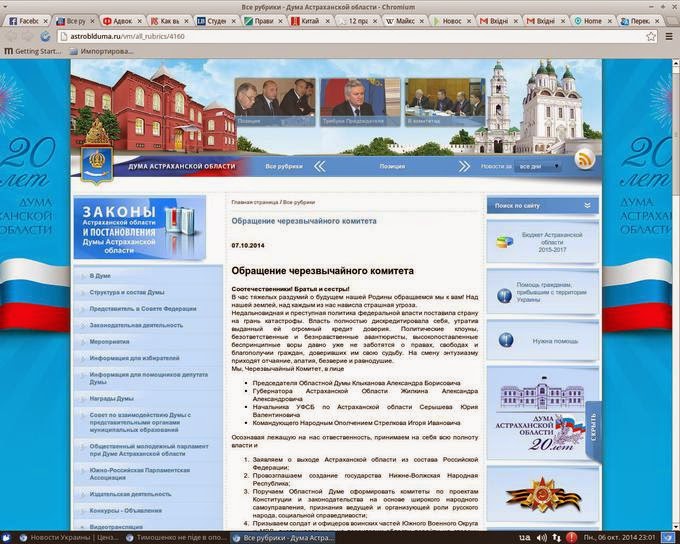

The announcement (pictured at the top of this article) appeared for about two hours on the website of the oblast’s legislature. It read, in part, “The short-sighted and criminal policies of the federal authorities have put the country on the brink of catastrophe. The authorities have fully discredited themselves, having lost the huge amount of trust given to them.” The declaration

was purported to be co-signed by several oblast officials, including Governor

Aleksandr A. Zhilkin, the Duma (parliament) chairman

Aleksandr B. Klykanov, the local

F.S.B. (state security, erstwhile

K.G.B.) head

Yuri V. Selyshev, and one

Igor Ivanovich Strelkov, identified as “Commander of the

People’s Militia.” (This, coincidentally or not, is the name of a colonel and former F.S.B. agent who earlier this year became a prominent paramilitary leader in the

Donetsk People’s Republic rebellion.)

The name of the Lower Volga People’s Republic republic echoes those of the two Kremlin-backed rebel governments which unilaterally seceded from

Ukraine earlier this year after the Russian invasion and annexation of

Crimea: the Donetsk People’s Republic and

Lugansk People’s Republic. (Three other declared republics, the

Kharkov People’s Republic in Ukraine’s northeast and so-called people’s republics in

Odessa and

Transcarpathia oblasts in western Ukraine, were never backed by any “facts on the ground” in the form of physical secession.) These “people’s republics” have less to do with actual state socialism or the rights of workers, as their names suggest, and more to do with recalling the symbols of a lost past when Ukraine was ruled from Moscow. In fact, they are run by undemocratic paramilitary juntas, with strings probably pulled from the Kremlin.

![]() |

| Aleksandr Zhilkin, Astrakhan’s governor, was not amused. |

Probably, the Lower Volga declaration evoked the Ukrainian rebel republics as a satirical observation of the fact that President

Vladimir Putin advocates federalism and balkanization in Ukraine while tightening central control over regional governments at home in Russia. But Astrakhan Oblast sits in a region with a separatist past. Comprising the Volga River delta the oblast’s capital is Astrakhan, sometimes called the southernmost outpost of the Russian world. To its east is the former Soviet republic of

Kazakhstan. (Kazakhs make up 16% of the oblast population, and

Volga Tatars another 7%; nearly all the rest are ethnic Russians.) To its southwest is the

Republic of Kalmykia, a member of the Russian Federation populated by Asiatic people following Tibetan Buddhism who after the collapse of the Soviet Union nearly seceded under the leadership of their charismatic president,

Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, a chess grandmaster and self-described U.F.O. contactee who boasted of psychic powers and chummed around with dictators like

Moammar al-Qaddafi and

Saddam Hussein. Just past Kalmykia and the Terek steppes is the volatile Caucasus region, where nearly every one of the dozens of separate indigenous ethnic groups has some form of separatist rebellion brewing. Across the Caspian Sea to the east are the Russian-populated

Transcaspia region in Kazakhstan, where

Cossacks have occasionally itched to secede from Kazakhstan and join Russia, and just beyond that the separatist

Republic of Karakalpakstan within independent

Uzbekistan. Just upriver from Astrakhan is the former territory of the

Volga German People’s Republic, which flourished before Soviet feelings toward its ethnic

Germans soured with

Adolf Hitler’s violation of his non-aggression pact with

Josef Stalin. (Both

Leonid Brezhnev and

Mikhail Gorbachev proposed restoring the republic until local Germanophobe Russians rose up against the idea.)

![]() |

| Coat-of-arms of the erstwhile Kuban People’s Republic |

More to the point, perhaps, just to the southwest of Astrakhan is

Krasnodar Krai, a mostly ethnic-Russian and ethnic-Ukrainian republic between Crimea and the Caucasus on the Black Sea, which includes Sochi, site of this year’s Winter Olympics. It is here that Russian authorities

last month jailed a leftist activist named

Darya Polyudova for holding a rally asking for more autonomy for Krasnodar Krai. Though she wasn’t asking for independence, she was arrested under a new law brought into force this year which makes the advocacy of separatism a crime. This August (

as reported on at the time in this blog) the Kremlin also cracked down on autonomy activists in

Siberia, who, like Polyudova, were in fact asking for nothing more than the autonomy guaranteed regions in the Russian constitution—rights which Putin has systematically eroded into almost nothing. Timed to coincide with the Siberian “day of action” that ended with police round-ups were autonomy rallies (

reported on at the time in this blog) in

Kaliningrad (Russia’s westernmost point, a formerly-German exclave wedged between

Poland and

Lithuania on the Baltic Sea), Yekaterinburg in

Sverdlovsk Oblast (

Boris Yeltsin’s home region, which attempted secession too after the Soviet collapse), and Krasnodar. In Krasnodar, the August rally organizers were calling for the reestablishment of the

Kuban Republic, a

Menshevik (anti-

Bolshevik) “people’s republic” which flourished briefly in the area during the Russian Civil War that followed the 1917 Communist revolution.

![]() |

| The autonomy activist Darya Polyudova is being held by the F.S.B. on separatism charges. |

Police arrested Polyudova and other activists on “hooliganism” charges at that August rally, after alleged pro-Kremlin provocateurs incited a brawl. Her family knew nothing of her whereabouts and waited in vain for her release when her one-month sentence ran out. Then, the

Public Monitoring Commission, a prisoners’ rights group in the area, located Polyudova a few days later in a

Federal Security Service (

F.S.B.—erstwhile

K.G.B.) lock-up where she had been transferred. Two other activists,

Vyacheslav Martynov and

Pyotr Lyubchenkov,

have sought political asylum in Ukraine. Polyudov’s group still advocates for “residents of Kuban whose rights are being violated, including the rights of ethnic Ukrainians.” (Needless to say, this is not a very comfortable point in history to be an ethnic Ukrainian living in Russia proper.)

![]() |

Some Cossack hosts formed brief-lived republics during the Russian Civil War

(shown here in relation to Astrakhan). |

After the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, many thought it was ethnic minorities like

Chechens and Tatars that might be the undoing of what was left of the Russian empire. But with those populations mostly beaten down by war and repression, it is ordinary Russians in the provinces who are today challenging Putin to live up to the “Federation” part of “Russian Federation.”

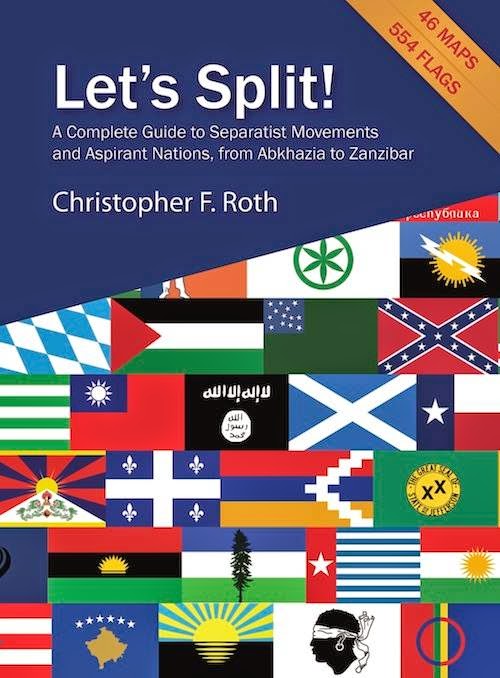

![]() |

| Current flag of Astrakhan Oblast |

[For those who are wondering, yes, this blog is tied in with my new book, a sort of encyclopedic atlas just published by Litwin Books under the title Let’s Split! A Complete Guide to Separatist Movements and Aspirant Nations, from Abkhazia to Zanzibar. (That is shorter than the previous working title.) The book, which contains 46 maps and 554 flags (or, more accurately, 554 flag images), is available for order now on Amazon. Meanwhile, please “like” the book (even though you haven’t read it yet) on Facebook and see this special announcement for more information on the book.]