It’s

being reported this week that a 59-year-old businessman from

Bulgaria has declared what he hopes will be the world’s newest independent country: the

Principality of New Atlantis (

Нова Атлантида). The businessman,

Vladimir Yordanov Balanov, has chosen as New Atlantis’s location a giant mass of floating volcanic pumice in the South Pacific measuring about 26,800 square kilometers—a bit smaller than

Haiti or

Belgium. (See the nation’s website

here.)

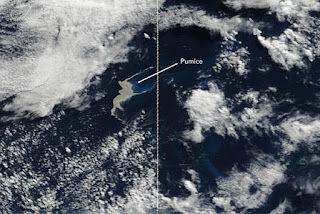

This rocky mass, generated by an underwater volcanic eruption,

was first reported in 2012 by

New Zealand’s navy, but it is not in that country’s territorial waters. It is at approximately 168ºW and 38ºS, due east of the country’s large North Island and due south of the self-governing overseas New Zealand territory of

Niue. It even lies significantly outside New Zealand’s exclusive economic zone.

![]() |

| The approximate location of “New Atlantis” in relation to New Zealand’s marine boundaries. |

Balanov

originally tried to convince his native Republic of Bulgaria to annex it—there are even indications he travelled there to plant a flag—but he got no expressions of interest either from Sofia or from the

European Union (

E.U.), of which Bulgaria is a member. (Bulgaria has never had any overseas territories. The E.U. does not have overseas territories itself other than overseas territories of specific member states. Some overseas territories of E.U. member states, such as

French Guiana and the

Canary Islands, are part of the E.U., while others, like

Greenland, the

Falkland Islands,

Curaçao, and

French Polynesia, lie outside the union while still being tethered to their mother countries. Nor has

any Eastern European country had overseas colonies, except for one: the

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, a part of modern

Latvia which enjoyed quasi-independence from the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries and briefly established colonies on

Tobago in the Caribbean—now half of independent

Trinidad and Tobago—and on

St. Andrews Island off the coast of what is now the

Republic of the Gambia. (St. Andrews has been renamed Kunta Kinteh Island, named for a fictional ancestor of

African-Americans in

Alex Haley’s 1976 novel

Roots, later played on television by

LeVar Burton.))

![]() |

| The flag of Liberland |

Other citizens of New Atlantis include, in addition to Balanov himself (whom,

the published constitution implies, will be New Atlantis’s founding hereditary prince), Balanov’s wife

Galina, as well as

Hristo Radkov, vice-president of the Bulgarian chapter of

Mensa, the international organization for high-I.Q. individuals. Balanov said that he was partly inspired by the establishment in April (

reported at the time in this blog) of the tiny libertarian micronation of

Liberland, on the border between

Serbia and

Croatia—a project headed by a Czech but largely, it seems, funded and staffed via

Switzerland.

![]() |

| In this map of disputed and unclaimed areas along the Serbian-Croatian border, the green area (“Siga”) is “Liberland,” while “Pocket 1” is the proclaimed territory of the Kingdom of Enclava (see below). |

Liberland is situated in a 3-square-mile area consituting one of several no-man’s-lands along the disputed border. The Liberland project had already inspired one other micronation: a group of tourists from Poland later that month

declared a

Kingdom of Enclava along the border between Croatia and

Slovenia. But the Slovenian foreign ministry quickly pointed out that “Enclava” was not

terra nullius but was actually undisputed Slovenian territory, even though admittedly the two states have not finalized the demarcation of their border. Enclava’s founder,

Kamil Wrona, calling himself King

Enclav I, then relocated his 134-citizen project to one of the true no-man’s-lands on the Danube River near Liberland (see map above). But Croatian and Serbian police have consistently done everything they can to shut down Liberland’s publicity stunts and flag-raisings.

![]() |

| The U.K.’s Sun tabloid has covered the Enclava story, since Britain, which has a large Polish population, is home to some who are connected the project. |

The Bulgarian founders of “New Atlantis” may yet prove to be making the same mistake that Liberlanders, Enclavans, and many other micronationalists have made—assuming that because a scrap of land is technically unclaimed, no state will interfere with the founding of an independent entity there. A libertarian Lithuanian-American real estate mogul named

Michael Oliver made this mistake in the early 1970s, when he barged tons of sand from

Australia to the Minerva Reefs, a set of low seamounts between

Fiji and

Tonga which did not poke above water for enough of the tidal cycle to be classified under international law as “territory.” But as soon as the reef was built up enough to pass legal muster,

Taufa’ahau Tupou IV, Tonga’s king, claimed it, and sent a naval vessel to eject Oliver and his nascent

Republic of Minerva. (Today, the reefs have eroded away once again to nothingness, but rival claims are still being made by Tonga, Fiji, and one “

Prince Calvin,” an American who says he is the “island’s” monarch.) Oliver’s similar “seasteading” project in

Palmyra Atoll, a

United States territory near

Hawai‘i, got even less far.

![]() |

| Spidermonkey Island, a floating island off the coast of Brazil invented by Hugh Lofting for the Doctor Dolittle novels, would not qualify as “territory” under international law because, like the New Atlantis pumice patch, it is not anchored to the ocean floor. Here, some whales under Dolittle’s command help move Spidermonkey Island to a more convenient spot. |

The “New Atlantis” mass of pumice stays above water throughout the tidal cycle, but it is not legally “land” either, since it is floating, not anchored. Whether New Zealand, its nearest neighbor, will tolerate any state-building there remains to be seen. Certainly, with no source of freshwater and no supply ports anywhere near by, it would be difficult to colonize. Perhaps Balanov was also inspired by the recent

Image Comics series titled

Great Pacific, which envisions a do-it-yourself nation called

New Texas founded atop an (actual existing, sadly) floating mass of plastic in the northern Pacific Ocean. The comics series, however, remains silent on many of the insuperable logistical barriers to such a project.

Balanov and compatriots may also want to consider a new name for their principality. The term

New Atlantis may well derive from the use of the name

Atlantis in

Ayn Rand’s 1957 novel-format libertarian manifesto

Atlas Shrugged, in which it, along with

Galt’s Gulch, was a label for the hidden mountain refuge in

Colorado where the world’s leading industrialists relocated themselves after dropping out of society so that they could live in peace and prosperity while the greedy, lazy “second-handers” bent on the redistribution of wealth suffered the utter implosion of the rest of the world’s now rudderless economy. (Just to clarify: in Rand’s novel, these industrialists were supposed to be the

good guys.)

![]() |

| Vladimir Balanov posing with the Bulgarian and New Atlantean flags |

Also, this isn’t even the first use of the name

New Atlantis. In 1964,

Ernest Hemingway’s brother

Leicester Hemingway founded his

Republic of New Atlantis on a bamboo raft lashed to an old Ford engine block floating off the coast of

Jamaica. And in 1624, Sir

Francis Bacon published a description of a fictional utopian “New Atlantis” on an island called Bensalem off the coast of

Peru.

![]() |

| The flag of Leicester Hemingway’s Republic of New Atlantis (1964) |

But the oddest thing about the name is that New

Atlantis is not in the Atlantic but in the

Pacific. Why don’t they call it New Lemuria?

![]() |

| The original, original New Atlantis, as envisioned by Sir Francis Bacon |

Thanks to Peppino Galiardi of the Kingdom of Cavaleria for alerting me to some sources and information for this article.