This past week a new nation was declared, on a spot of land in the murkily demarcated border zone in the region of Slavonia where the Republic of Serbia and the Republic of Croatia meet. But it is not a Serb or Croat behind the project, but a Czech one, and it is more ideological than ethnonationalist. The founder, Vít Jedlička, on April 13th, announced the independence of the Free Republic of Liberland (Svobodná republika Liberland) on a parcel of land on the west bank of the Danube (the mostly Croatian side) around Gornja Siga, an area which is a de facto no-man’s-land since neither side asserts a claim on it.

|

| Gornja Siga, in green, is only one of several parcels of land along the Croatian–Serbian frontier with no clear status. |

The self-declared President Jedlička—a 31-year-old local official of the Czech Republic’s marginal, libertarian Free Citizens’ Party (Strana svobodných občanů), which is hostile to Czechs’ membership in the E.U.—admits that there are no “facts on the ground,” as it were, in Gornja Siga itself, only a declaration made from afar. There was also an impromptu, unauthorized flag-raising on Liberlandic territory. But although, as Jedlička told Time magazine, “it started a little bit like a protest, ... it’s really turning out to be a real project with real support.”

|

| A Czech ZZ Top tribute band rocked a recent Free Citizens’ Party rally. |

One of the few requirements for citizenship is a lack of a Nazi, Communist, or “extremist” past. (Presumably, radical anarcho-libertarianism is, for these purposes, not classified as “extremist.”) It is unclear at this point whether anyone currently lives in the designated territory of Liberland, but aerial photos suggest that it its status as terra nullius is de facto and not just de jure. The Serbian and Croatian governments have not yet responded to the declaration, though Egypt’s foreign ministry has already warned Egyptians against trying to move there. Bitcoin, reportedly, is to be the national currency.

Originally, Jedlička’s idea was borne of frustration at the marginalization of libertarian ideas in the Czech Republic—even though his country is more committed to free-market principles than almost any in the world. The Free Citizens’ Party has one seat in the mostly powerless European Parliament and none in the Czech legislature. “I’m still going to be active in Czech politics,” he added. “I would probably resign and let somebody else run Liberland for me if there was a chance to do political change in the Czech Republic.”

Most high-profile micronations can be found in the English-speaking world (especially Australia, for some reason) and Scandinavia, with some in the rest of western Europe as well. The Balkans have vanishingly few so far. But the Czech Republic is no stranger to the phenomenon. In 1997 a Czech photographer named Tomáš Harabiš founded a Kingdom of Wallachia (Valašské Kralovství) in the republic’s Moravian Wallachia region (not to be confused with Romania’s region of Wallachia), and the noted Czech comic film actor Bolek Polívka was crowned King Boleslav the Gracious (later deposed). There are, on paper, 80,000 “Wallachian” citizens.

|

| Moravian Wallachia’s King Boleslav the Gracious |

|

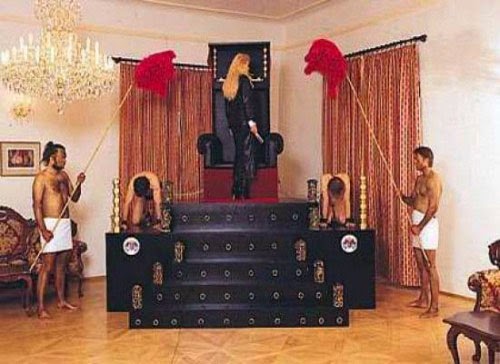

| Four worthless vermin—I mean, citizens—pay tribute to Queen Patricia I in the erstwhile Other World Kingdom. |

|

| Milton Friedman (left; actual size) also had Czechoslovak blood in his veins. |

Oliver’s most tragicomic attempt at a libertarian state had been in the early 1970s, when he barged tons of sand from Australia to the Minerva Reefs, a set of low seamounts between Fiji and Tonga which did not spend enough of the tidal cycle above water to be classified under international law as “territory.” But as soon as the island was built up enough to pass legal muster, Taufa’ahau Tupou IV, Tonga’s king, claimed it, sent a naval vessel to eject Oliver and his nascent Republic of Minerva. (Today, the reefs have eroded away once again to nothingness, but rival claims are still being made by Tonga, Fiji, and one “Prince Calvin,” an American who says he is the “island’s” monarch.) Oliver’s similar “seasteading” project in Palmyra Atoll, a U.S. territory near Hawai‘i, got even less far.

Another libertarian seasteading pioneer was Werner K. Stiefel, an American drugs mogul who in 1969 tried to start a utopia by fomenting a rebel movement in the uninhabited Prickly Pear Cays during a brief separatist rebellion in the British colony of Anguilla. After British troops put an end to that, Stiefel tried landfilling to seastead something called “Operation Atlantis” on Silver Shoals, disputed specks of land between Haiti and the Bahamas. Atlantis was a name for the invisibility-cloaked libertarian refuge in the Rockies in Ayn Rand’s influential 1957 novel Atlas Shrugged. (For more on seasteading, see articles from this blog on the Principality of Sealand, here and here.)

|

| An artist’s rendering of the planned Principality of New Utopia, in the western Caribbean |

|

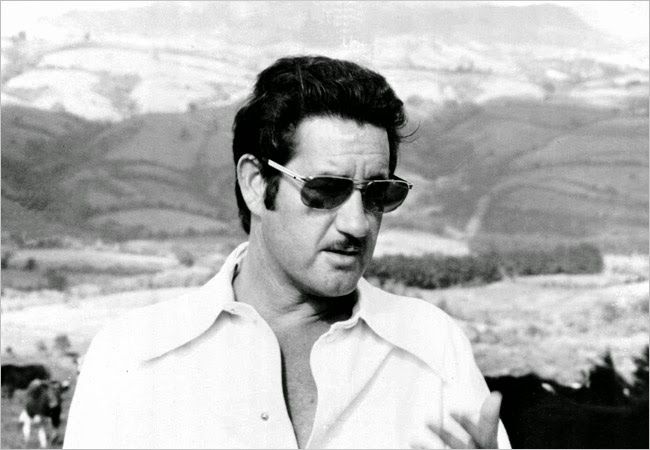

| Would you buy a used micronation from this man? Robert Vesco was never a big fan of government regulation. |

Of all these past attempts, President Jedlička might do well to note the fate of the Republic of Minerva. He chose the Minerva Reefs because they were pieces of “land” that had fallen between the cracks of two established states, Fiji and Tonga, which were not claiming them. But then as soon as the project got rolling, the neighbors changed their minds and wanted in on the project. That ended badly. Imagine how much uglier it could get if Jedlička not only lost his utopia invaded but found himself literally in the middle of a renewed territorial battle between Serbs and Croats. Liberland might be in a pretty spot, but it’s one of the most volatile borders in recent history.

Thanks to Trena Klohe and Alexander Velky for first alerting me to this story.

[You can read more about many of these and other separatist and new-nation movements, both famous and obscure, in my new book, a sort of encyclopedic atlas just published by Litwin Books under the title Let’s Split! A Complete Guide to Separatist Movements and Aspirant Nations, from Abkhazia to Zanzibar. The book, which contains 46 maps and 554 flags (or, more accurately, 554 flag images), is available for order now on Amazon. Meanwhile, please “like” the book (even if you haven’t read it yet) on Facebook and see this special announcement for more information on the book.]